Q.

Dear Olivia,

Two and a half years ago, my best friend of a decade ghosted me. Outside of my family, she was undoubtedly the most important person in my life. Before she disappeared from my life, we were college students living together; when I envisioned my post-grad future, with so much uncertainty ahead, the only constant I could imagine was her. We were close in the kind of way that most people never experience, that sometimes makes others uncomfortable -- the kind of closeness that stems from becoming inseparable at 13. Our lives were deeply intertwined, and it was genuinely shocking, to me and to everyone else in my life, when she slowly stopped responding to my texts and eventually told me she "wasn't sure what she was looking for" (the type of language you send to a Hinge match after two dates, not to your best friend).

I'm in therapy, and I've come to accept that our friendship, like all relationships, was not perfect. I've struggled with mental illness for as long as I've been alive, and I recognize the ways it's made me mistreat others. We fought and made up countless times, and before she ghosted me, she started dating the person she's still with, a man who was quite rude to me and who I suspect may have wanted to drive a wedge between us.

I could go on and on about the nuances of our relationship, about how important she was to me, about all of the information I've gathered about her life in the aftermath--much of which alludes to her being in a toxic relationship, which has me feeling both satisfied and concerned--but what I'm really stuck on is getting over it. Her birthday is in a few days, and I can feel my obsession flaring up. Today I caught myself on a stranger's wedding website after seeing their name in one of her Venmo transactions.

I want to stop thinking about her, and, when it inevitably happens, I want be able to reflect on our friendship with objectivity. These were the formative years of my life, and there was so much good alongside the bad. I want to stop hunting for glimpses of her life in Instagram posts and conversations with mutual acquaintances. I've never been good at letting things go, but I feel crazy for still being so torn up about it... and even crazier when I think about her just living her day-to-day life and not feeling the same.

Unlike with a romantic breakup, I haven't been able to find much comfort in friends or media -- my situation is not relatable to most people, especially because it didn't end in a fight or falling out. But I'm hoping you may have some advice on how to move on from something like this. I live a different life now, in a new city with a steady circle of close friends, and it's a good one... yet I still find myself spiraling like this, far more often than I'd like.

Much love from a longtime fan & sincere apologies for the lengthy note,

P

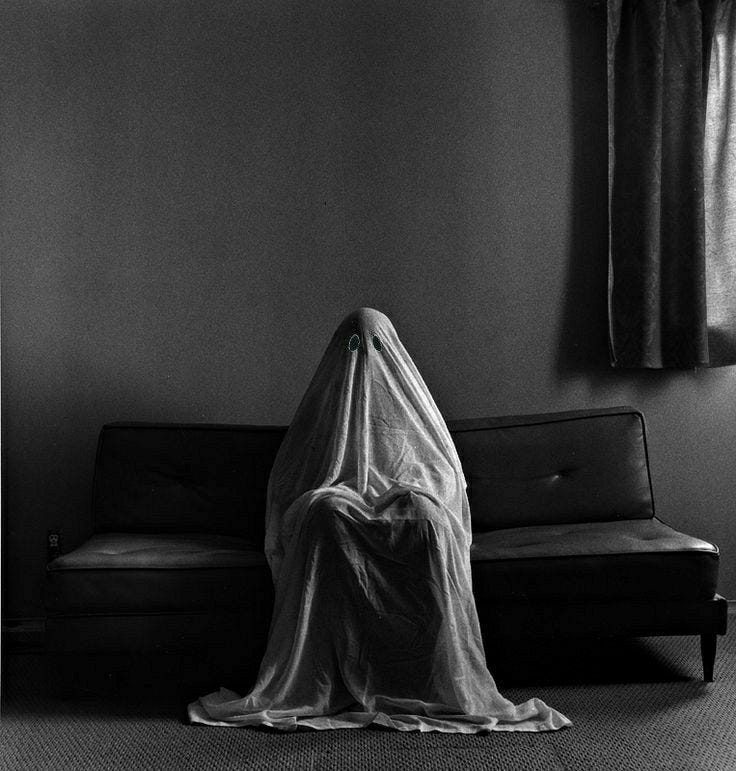

photo by anne grant

A.

Dear P,

Let’s start with the obvious.

Ghosting doesn’t happen in a vacuum but that doesn’t make it justified. You’ve acknowledged that your friendship with this person had weathered some real cuts and that the ~fizzle into silence~ method of separation was likely a result of these cuts feeling apparently unsurvivable to the person who ghosted you. You’re right to say that your situation isn’t the most common example of ghosting due to it being a friendship, but here’s this small offering: all ghosting that happens in longterm relationships (platonic or otherwise) follows this same formula. Repeated conflict + chronic avoidance + unhealed resentment = abrupt abandonment without verbalized reason aka ghosting.

The reason I am suddenly doing math is because I want to help you distance yourself from the ziggurat of fault, blame, and shame, and I want you to focus on the elements that are simply a product of predictable human behavior. That isn’t to say that the intricacies of your friendship don’t matter, but it is to say that meticulously revisiting those intricacies in search of some glowing explanation is what is keeping you from healing. There are reasons she was upset with you. There are things you did to hurt her. And vice-versa. This is what we can expect from any relationship that follows us through the majority of our lives. What we owe each other in the end is not unwavering commitment. What we owe each other—in the likely and painful end—is communication. In the end, we owe each other an ending.

Which is why, Dearest P, I want to reassure you that you are not crazy for being torn up but also, I don’t blame you for going crazy over all of this. Yes, there’s a difference. Ghosting seemingly leaves one person with all of the answers, and one person with total speculation. As the ghoster, if someone were to ask her why your friendship ended, she would likely be able to tell them in clear and concise detail. As the ghostee, if someone were to ask you this same question, you would probably stumble through the answer with a lot of “I guess…” and “Maybe…” and “What I think happened was…”. Having to spend the immediate aftermath of a break-up searching for the why only delays our true ability to grieve, and that is the real crime of ghosting. It robs us of reason, and without reason we go, say it with me, totally fucking crazy.

Alas, we can’t beg the gods for reason and surely we can’t rely on your ex-friend to provide it. So now, we’re left to build our own. Which brings us back to math. The reason you were ghosted, the reason your friendship ended, is because in lieu of facing the tedious and painful conversations that needed to happen, your former friend chose to follow an unfortunately common formula of avoidant human behavior. This fact does not absolve you of any and all wrongdoing, nor does it make her the ultimate villain, but what it does do is define the seemingly undefinable end of your friendship. It gives you an answer. And that is how we find closure.

But another tricky element of the ghoster/ghostee dynamic is the illusion of power. You said it yourself: I feel even crazier when I think about her just living her day-to-day life and not feeling the same. But this stability you’re imagining for her, P, is not real. Really, the lack of closure is haunting her, too. Sure, she might be able to more quickly answer the question of why your friendship ended, but she probably is also inclined to withhold exactly how it ended. You notice how we meet a lot of people who have been ghosted but not a lot who have done the ghosting? That’s because no one wants to admit they followed the formula. We want to be evolved, we want to be unique, we want to be clean. And so we focus on the why’s, we say, “She did this and this and this, and I couldn’t take it anymore.” We watch our audience nod in empathetic unison. And we conveniently leave out the part where we disappeared from a longtime friend’s life without conversation. Then the curtains close and we’re the hero.

I don’t envy her position. The guilt and shame that follows her must be painful. She misses you too and she hates knowing that if she were to come back for a conversation, it would now be her who owes you an apology first. You can’t find representation in the media, meanwhile all the representation she sees paints her as the bad guy. Friends and podcasters and characters on TV lamenting about ghosting, how evil it is. All she’s left with is her own messy understanding of why she did what she did, a haphazard construction of reason that likely leaves her feeling dissatisfied.

In the end, she’s denied herself an ending, too.

So what if we stopped looking for an ending or hoping for a new beginning or asking for an answer to what already happened? What if instead, we embraced this strange, directionless in-between where a friendship pauses indefinitely because one person on the tandem bike feels unable to face that conversations have to be had in order to keep riding? And so, she chooses to simply get off and walk away, some small part of her hoping you’ll still be there, propping the bike up on your hip, when she decides to come back. Maybe that’s all avoidance is, anyway—a misguided attempt at preservation. You and I both know that isn’t how things work. You won’t be there waiting with the bike when she comes back—she will have to go looking. She will have to call your name.

But what will be there is the bike—all those years you spent together in the form of a rusty tandem bicycle—lying on its side in the dirt. Maybe no one will ever pick it up and ride it again, maybe they will, but regardless, it’s there. It always will be. You don’t have to keep checking. You don’t have to make sure it still works. You don’t have to wait nearby. The bike will be there. Right now, she is somewhere else. Now keep walking.

Love,

Olivia in a small house

such a painful experience. I have had to tell myself to stop being the person who is willing to take them back with open arms.